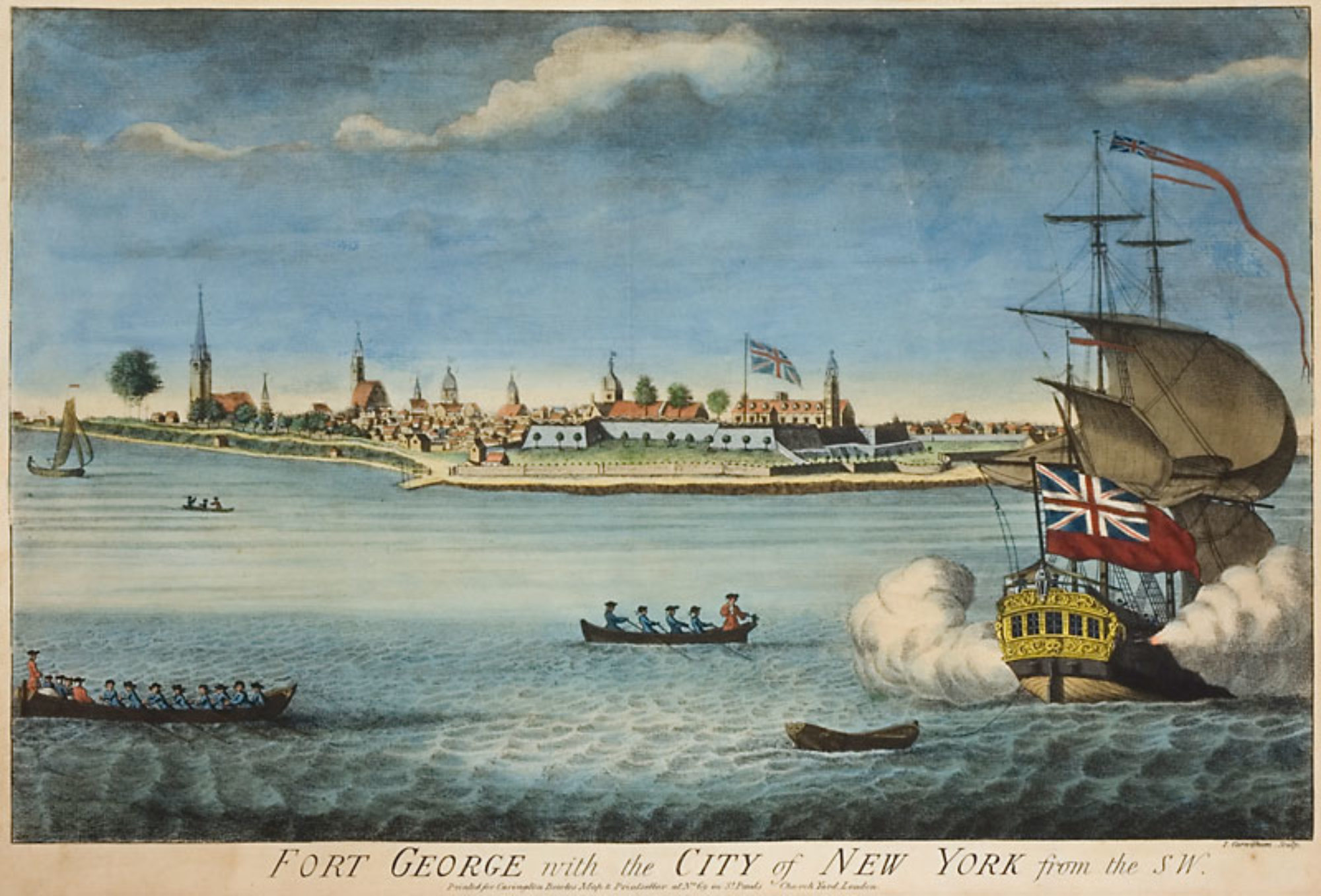

George Washington’s aide-de-camp receives dispatches of the British anchoring off of Staten Island and writes of the activity in and around Sandy Hook and New York Bay. These dates coincide with the dates of British soldier Archibald Robertson‘s diary, and is a wonderful contrast of the belligerents and their contrasting observations of the impending confrontation between the Americans and the British Empire’s powerful Army and Navy.

|

1939.503 Samuel B. Webb by Artist/Maker: Charles Willson Peale

Date: 1779, 1790 Medium: Watercolor on ivory, gold

From: New-York Historical Society |

June 28th—This Morning we hear our Cruizers off the back of Long or Nassau Island, have retaken four prizes-which the Greyhound Man of War had a few days before taken-The sailors inform that General Howe was on board the Greyhound and had arrived at Sandy-Hook; that 130 sail of transports, &c., were to sail from there for this place the 9t!t Inst If this be true, we may hourly look for their arrival.*

Agreeable to yesterday’s Orders, Thomas Hicky was hang’d in presence of most of the Army-besides great numbers of others-spectators-he seemed much more penitent than he was at first.**

Saturday, 29th June—This morning at 9 o’Clock, we discovered our Signals hoisted on Staten Island, signifying the appearance of a fleet At 2 oClock P. M. an express arrived, informing a fleet of more than one Hundred Square rig’d vessels, had arrived and anchored in the Hook—This is the fleet which we forced to evacuate Boston ; & went to Halifax last March— where they have been waiting for reinforcements, and have now arrived here with a view of puting their Cursed plans into Execution. But Heaven we hope and trust will frustrate their cruel designs—a warm and Bloody Campaign is the least we may expect ; may God grant us victory and success over them, is our most fervent prayer. Expresses are this day gone to Connecticut, the Jerseys, &c, to hurry on the Militia.

July 1st—By express from Long Island, we are in formed that the whole fleet weighed Anchor and came from Sandy Hook, over under the Long Island shore, and anchored ab’. half a mile from the shore—which leads us to think they mean a descent upon the Island this Night. A reinforcement of 500 men were sent over at 9 oClock this Evening to reinforce the troops on Long Island under General Green—We have also received Intelligence that our Cruisers on the back of Long Island, have taken and carried in one of the enemie’s fleet laden with Intrenching Tools.

N. Y. July 2nd—At 9 oClock this morning the whole Army was under Arms at their several Alarm Posts, occasioned by five large Men of War coursing up thro: the narrows—We supposed them coursing on to attack our Forts—never did I see Men more chearfull; they seem to wish the enemies approach—they came up to the watering place, about five miles above the narrows, and came too—their tenders took three or four of our small Craft plying between this and the Jersey Shore-At 6 oClock P. M. about 50 of the fleet followed and anchored with”the others–Orders that the whole Army lie on their Arms-and be at their Alarm Posts before the Dawning of the Day. A Warm Campaign, in all probability, will soon ensue, relying on the Justice of our Cause, and puting our Confidence in the Supreme being, at the same time exerting our every Nerve, we trust the design of our enemies will be frustrated.

July 2nd [3rd]—This day Arrived in Camp, Brigadier General Mercer, from Virginia, being appointed and ordered here by the Honl Continental Congress[1]

likewise General Herd with the Militia from New Jersey[2] by order of his Excellency Genl Washington.

Thursday, July 4th—Last night-or rather at daylight this morning-we attack’d a sloop of the enemies mounting eight Carriage Guns-She lay up a small river, which divides Staten Island from the main -call’d the Kills. We placed two 9 pounders on Bergen Point-and soon forced the crew to quit her by the shrieks, some of them must have been kill’d or wounded-the sloop quite disabled.

N. Y. July 7th—By several Deserters from the fleet and Army on Staten Island, we learn that the number of the enemy is abt. 10,000; that they hourly look for Lord Howe from England with a fleet, on board of which is 15 or 20,000 men ; that they propose only to act on the defensive ’till the arrival of this fleet, when they mean to open a warm and Bloody Campaign, and expect to carry all before them-but trust they will be disappointed.

N. York, July 9th, 1776—Agreeable to this day’s orders, the Declaration of Independence was read at the Head of each Brigade; and was received by three Huzzas from the Troops-every one seeming highly pleased that we were separated from a King who was endeavouring to enslave his once loyal subjects.[3] God Grant us success in this our new character.

July 10th, 1776—Last night the Statue of George the third was tumbled down and beheaded-the troops having long had an inclination so to do, tho’t this time of publishing a Declaration of Independence, to be a favorable opportunity-for which they received the Check in this day’s orders.[4]

_______________________________________

*These prizes were taken by the armed sloop Schuyler, and one other cruiser, Howe arrived on the 25th.

**Thomas Hickey, a member of the General’s guard, was implicated in the “conspiracy,” and on trial was convicted of having enlisted into the British service and engaged others. He was sentenced to be hung. “The unhappy fate of Thomas Hickey, executed this day for Mutiny, Sedition and Treachery, the General hopes will be a warning to enry soldier in the army to avoid those crimes and all others, so disgraceful to the character of a soldier, and pernicious to hit country, whose pay he receives and bread he eats. And in order to avoid those crimes, the most certain method is to keep out of temptation of them, and particularly to avoid lewd women, who, by the dying confession of the poor criminal, first led him to practices which ended in an untimely and ignominious death”-Orderly Book, 28 June, 1776.

[1] Hugh Mercer. He was sent to command the operations in New Jersey.

[2] Nathaniel Heard. He had just been sent to Staten Island to drive off the stock.

[3] “The Honr: the Continental Congress, impressed by the dictates of duty, policy and necessity, having been pleued to dissolve the Connection which subsisted between this country and Great Britain, and to declare the United Colonies of North America free and independent STATES : The several brigades are to be drawn up this evening on their respective parades, at six o’clock, when the declaration of Congress, showing the grounds and reasons of this measure, is to be read with an audible voice.”

“The General hopes this important event will serve u a fresh incentive to every officer and soldier, to act with Fidelity and Courage, u knowing that now the peace and safety of this country depends (under God) solely on the success of our Arms: and that be is now in the service of a State, possessed of sufficient power to reward his merit, and advance him to the highest Honors of a free Country.”-Orderly Book, 9 July,1776.

[4] “Though the General doubts not the persons who pulled down and mutilated the Statue in the Broadway lut night were actuated by zeal iu the public cause, yet it has much the appearance of a riot and want of order in the army, that be disapproves the manner and directs that in future these things shall be avoided by the soldiery, and left to be executed by the proper authority.”-Orderly Book, 10 July, 1776.

________________________________________________

All quotes from: Commager, Henry S., and Richard B. Morris. The Spirit of ‘seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution As Told by Participants. New York: Harper & Row, 1967. Print.

Like this:

Like Loading...