|

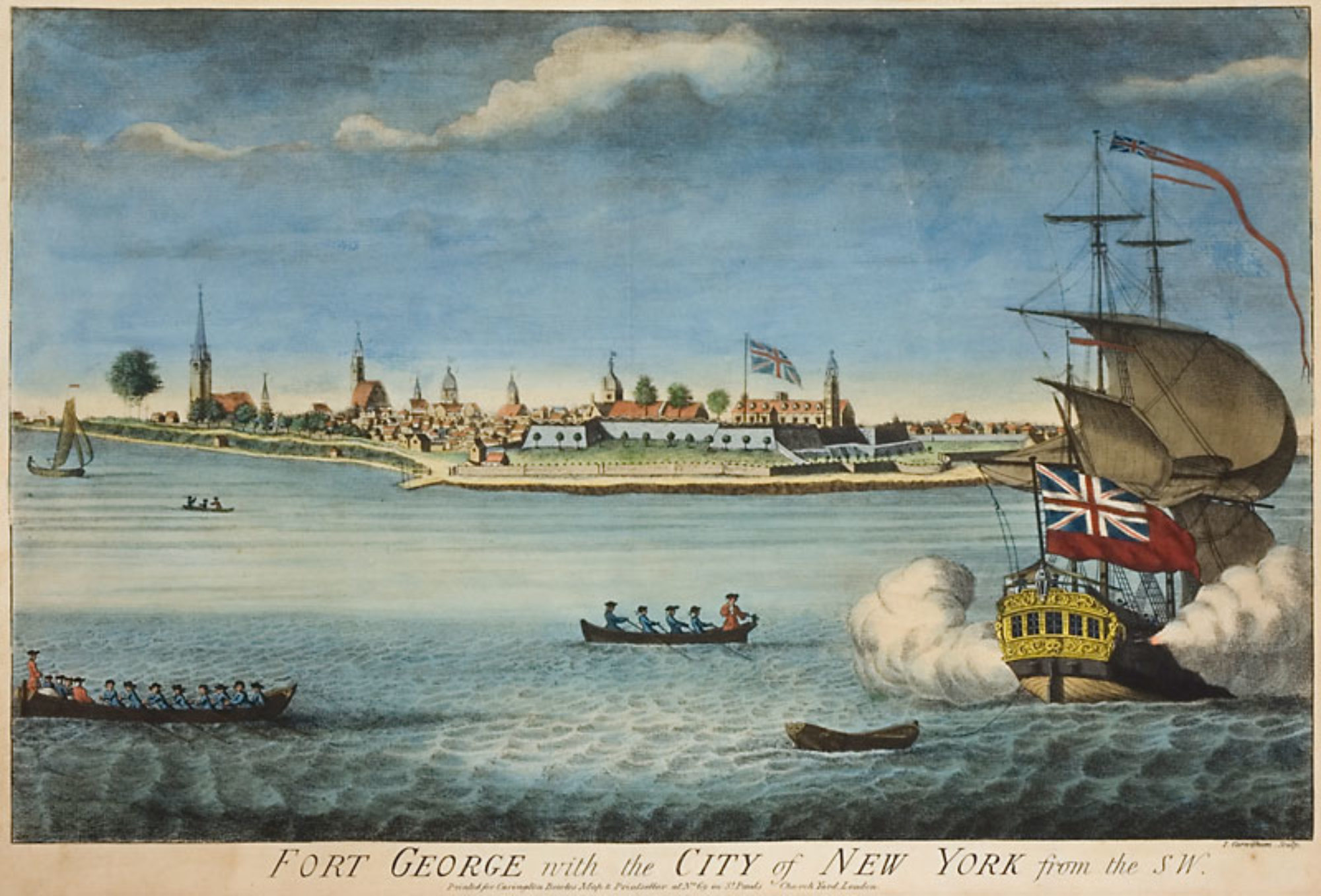

In August of 1919, an archaeological dig on Cocheran’s Hill found a button of the King’s Own, or Fourth Foot regiment (see painting below) which unit was a part of the amphibious landing at Gravesend Bay in summer of 1776.  |

Colonel Richard St George Mansergh (born 1757) (the name of ‘St George’ following ‘Mansergh’ was assumed on inheriting his maternal uncle’s property, Richard St George Mansergh-St George) was a British Army officer and magistrate of County Cork, Ireland.

Family

His maternal grandfather was Sir Richard St George, whose grandfather was Sir George St George of Carrickdrumrusk and was ancestor of the Barons St George. His two brothers were Oliver and George. Richard was the ancestor of the St Georges of Woodsgift in County Kilkenny. The St Georges were originally from Cambridgeshire, England, who were granted lands in the Headford area by the Cromwellian Commissioners in 1666, much of it formerly held by the Catholic Skerrett family. Their ownership of lands was extensive in the counties of Galway, Roscommon, Limerick and Queen’s county (county Laois) confirmed by a patent dated October 26, 1666. The family bore a coat of arms blazoned Argent a Chief Azure overall a Lion rampant Gules crowned Or. Gallowshill in Carrick-on-Shannon, Hatley Manor and Holywell are the ancestral family manor houses.

Education

He was educated at Westminster School before entering Middle Temple in 1769. Admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1771, he graduated with a BA in 1775.[1] He was friends with the painter Henry Fuseli and the poet Anna Seward and has been reputed to have been a very accomplished artist, lampooning the political figures and events of the day in sketches and watercolors.

In 1771, he inherited his uncle’s estate and added ‘St. George’ to the end of his surname.

Early military career

|

He began his military career in late 1775 by purchasing a cornet’s commission in the 8th (The King’s RoyalIrish) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons. After serving three months, he retired, but had signed up again by obtaining a position as an Ensign in the 4th Regiment of Foot at the outbreak of war in America.

His regiment joined General William Howe in the Battle of Long Island in 1776, and at Fort Washington.

While at Staten Island, he eventually purchased a lieutenancy in the 52nd Regiment of Foot in December 1776.

After lay-waying in Nova Scotia in early 1777, he participated in the Philadelphia campaign of 1777, seeing action at the Battle of Brandywine and the Battle of Germantown where he was wounded. He was shot in the head and trepanned (a portion of his skull was removed) and fitted with a silver plate to cover the hole, requiring St. George to wear a black silken cap for the remainder of his life. Xavier della Gatta’s painting of the Battle of Germantown depicts a fellow private, Corporal George Peacock, carrying the wounded St. George on his back from the battle (see illustration below). Mansergh-St George recounted:

After lay-waying in Nova Scotia in early 1777, he participated in the Philadelphia campaign of 1777, seeing action at the Battle of Brandywine and the Battle of Germantown where he was wounded. He was shot in the head and trepanned (a portion of his skull was removed) and fitted with a silver plate to cover the hole, requiring St. George to wear a black silken cap for the remainder of his life. Xavier della Gatta’s painting of the Battle of Germantown depicts a fellow private, Corporal George Peacock, carrying the wounded St. George on his back from the battle (see illustration below). Mansergh-St George recounted:

“a most infernal fire of cannon and musket–smoak–incessant shouting–incline to the right! Incline to the Left!–halt!–charge!…the balls ploughing up the ground. The trees cracking over ones head, The branches riven by the artillery. The leaves falling as in autumn by grapeshot.”

He returned to New York in June 1778. He was eventually promoted to captain in the 44th Regiment of Foot in 1778. By the end of the war he was serving as an aid to Sir Henry Clinton. He exchanged that commission for the same rank in the 100th Regiment of Foot on 4 May 1785, only to finally retire from the regulars on 18 May.

|

Return to Ireland after the American war

|

After being mustered out in May 1785, he returned to Ireland from America and married Anne Stepney of Durrow, County Laois (then Queen’s County) in 1788, and within three years they had two sons, Richard James and Stepney St George. Mansergh St George was an active, local magistrate appalled by the poverty that he found on his estates in County Cork and County Galway. His response to this was an Account of the State of Affairs in and About Headford, County Galway, which laments the condition of the Irish peasantry, and whilst considering establishing a linen industry to improve matters, doubts the willingness or the ability of his tenants to make the enterprise work. Mansergh St George’s wife had died in 1791, leaving her husband a widower with two infant children, and he wished to have a portrait painted of himself (see illustration at right below) as a monument to his grief for her. The eventual result of the commission is the full-length portrait by Hugh Douglas Hamilton now in the National Gallery of Ireland, in which Mansergh St George, in his Irish Light Horse Militia uniform, leans in an attitude of grief against a classical tomb inscribed Non Immemor.

Irish rebellion of 1798

By the late 1780s, the vast mountainous tract of land between Cork and Tipperary was overseen by the only active magistrate, which was Col St George himself. The local peasants had been indiscriminately cutting down trees for pike handles on the estates, as the gentry looked on in terror for fear of insurrection by their own tenants. The Colonel had written a confidential letter to the Castle describing “a gentleman about a quarter of a mile from this passively observed the people cutting down fifty of his trees in Daylight in view of his house.”

|

St George had been dining with the Earl of Mountcashel’s at Moor Park, and freely expressing his views about his detestation of treason and rebellion. It is plausible that a servant may have reported these discussions to the assassins, so as they may have been ready and laying in wait for the Colonel. On 12 February 1798, at the outbreak of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 thirty republicans from North Cork and South Tipperary attacked the house of Jasper Uniacke, Esq, the Colonel’s tenant and administrator, and according to the Hibernian Chronicle “demanded that St. George Mansergh, who was then in the house, should be sent out to them; this being refused, they rushed in to seize him, on which he shot one of them dead, which so exasperated the rest, that with pitchforks, and other weapons,” was “barbarously murdered” along with his servant with a rusty scythe. The newspaper article continues to describe the murder: “And to add to their inhumanity, they wounded Mrs. Uniacke, while in the act of saving her husband, so that she lies dangerously ill.” She survived and identified the assailants, John Haye and Timothy Hickey, at their trial in 1798: both men were found guilty and executed at Araglin.[2]

Footnotes

[1]Venn, J.; Venn, J. A., eds. (1922–1958). “Mansergh (post Mansergh-St George), Richard St George”. Alumni Cantabrigienses (10 vols) (online ed.). Cambridge University Press.

[2]Annual Register …for the year 1789, 1800, pp. 32-3.

References

“The True Briton,” The Times, p. 3 (16 February 1798).

Copyrighted material. All Rights Reserved. Nick Matranga @ 2012-2013.

Nice article. I'm interested to know more about the source of the Illustrations attributed to Richard Mansergh St George.

I believe I found them at The National Gallery in London. Or, the Archives at Kew.

Warfare is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good read.