The somewhat secluded nature of Staten Island in the 17th and 18th centuries afforded its citizens with relative peace and prosperity after the first Dutch settlers battled with the local Indians and struggled to gain a foothold at Oud Dorp (Old Towne).

1775

Since there were no delegates being sent to the Second Continental Congress in 1775, Richmond became notorious for its Loyalist sympathies. Christopher Billoppe, the wealthiest of the Loyalists, owned Bentley Manor at the extreme southern tip of the Island. The opinion which George Washington had formed of the people of Staten Island, as well as of their immediate neighbors at Amboy, may be learned from the following extract from one of his letters:

“The known disaffection of the people of Amboy, and the treachery of those of Staten Island, who, after the fairest professions, have shown themselves our inveterate enemies, have induced me to give directions that all persons of known enmity and doubtful character should be removed from these places”

-

photo: Nick Matranga

The New York Provincial Congress had swayed the merchants and farmers to appoint members to a committee of safety or risk continuing their goods being boycotted by other local towns in New Jersey.

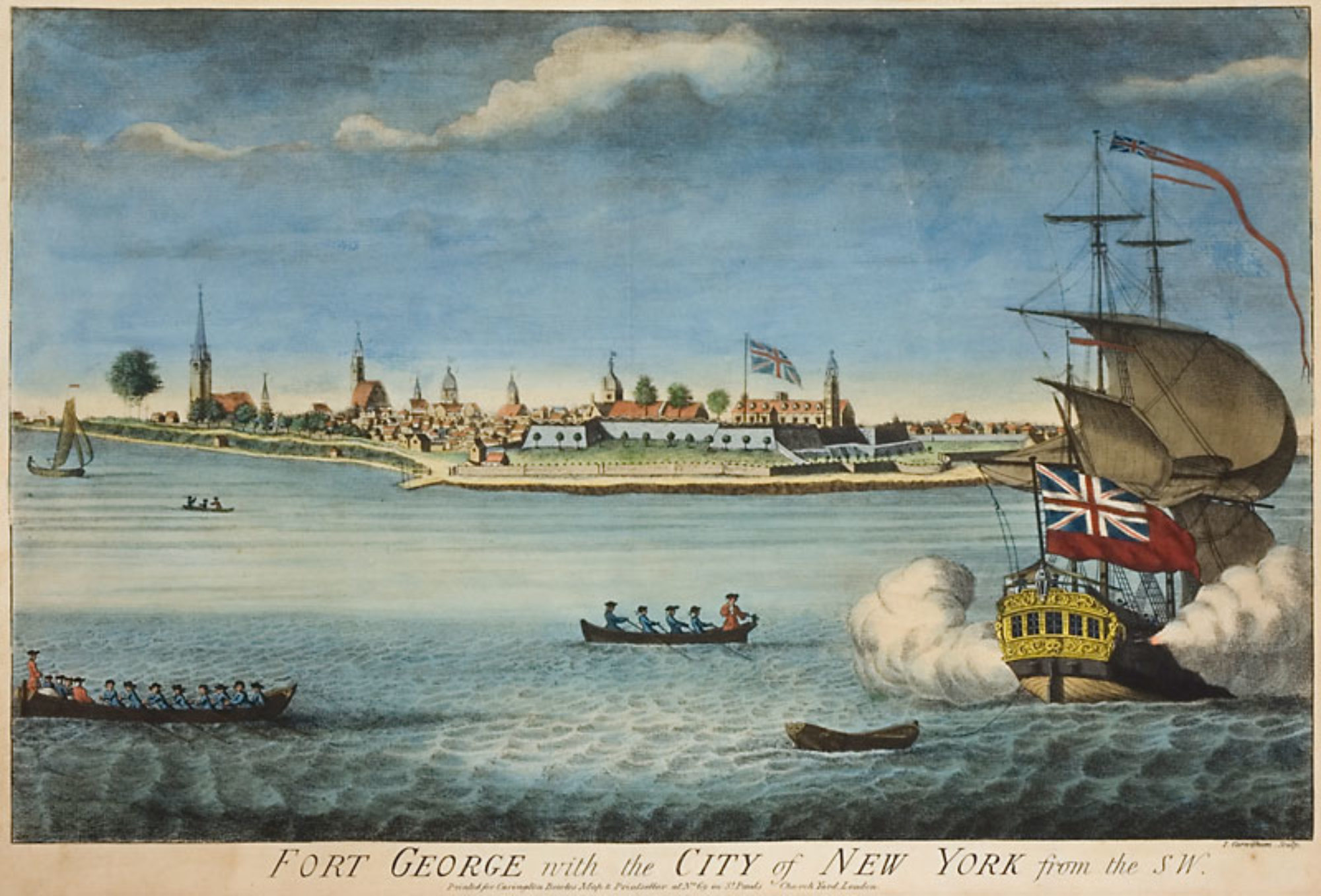

In June 1776 the ships began to arrive off of Staten Island, and slowly entered the Narrows into Upper New York Bay. By the beginning of August, an estimated 30,000 ships were anchored in the harbor and directly off of Staten Island. The soldiers disembarked and started to set up camp all over the Island, chopping down the forests for their cabins and fire wood and foraging for cattle and food on the small farms that dotted the Island. General Howe had explicitly forbade foraging and stealing from the local farmers, but the soldiers served themselves to the generous amounts of apples, peaches and cherries from the numerous orchards along the south shore.

General Howe set up his headquarters near the Decker Ferry on the shore road along the Kill van Kull at the Adrian Bancker house. British troops were billeted in the Rose & Crowne Inn at New Dorpe, where the Olde King’s Highway crosses the main road of the town. The Black Horse Tavern nearby was also commandeered for the use of the Officers and their Aides-de-Camp while stationed on the Island.

General Howe set up his headquarters near the Decker Ferry on the shore road along the Kill van Kull at the Adrian Bancker house. British troops were billeted in the Rose & Crowne Inn at New Dorpe, where the Olde King’s Highway crosses the main road of the town. The Black Horse Tavern nearby was also commandeered for the use of the Officers and their Aides-de-Camp while stationed on the Island.

A Hessian soldier named Baurmeister recorded a description of the British forces encamped at Staten Island for the 14th and 15th of August. His division had sent 132 soldiers to the Hospital encampment, due to scurvy:

“We found the Eglish troops, which had been driven out of Boston encamped on Staten Island on eight different heights.

At Amboy Ferry, Lieutenant General Clinton with two brigades and half of an artillery brigade.

Between Amboy Ferry and the Old Blazing Star (now Rossville), Brigadier General Leslie with three brigades and half an artillery brigade.

At the Old Blazing Star, Brigadier General Farrington with two brigades and two 12-pounders and also half a troop of light dragoons to carry dispatches.

At the New Blazing Star (at Long Neck, now Travis), Brigadier Generals Smith, Robertson and Agnew with three brigades and the other half of light dragoons.

At Musgrower’s Lien [?](Lane?), Lieutenant General Percy and Brigadier general Erkine with two brigades and four 6-pounders and one officer and twnty-five light dragoons.

At the point opposite Elizabeth town Ferry, Major General Grant with one brigade, two light guns, and fifteen dragoons.

At the Morning Star (the country seat of Henry Holland, on the northern side of the island), Lieutenant General Cornwallis with two and a half brigades, six 12-pounders, four howitzers, and fifteen dragoons.

At Decker’s Ferry (now Port Richmond), Major General William James with the 37th and 52nd Regiments and two light guns.

To the right of Decker’s Ferry, in a country house close to the shore opposite New Jersey, Major General Vaughan with six grenadier battalions, the 46th Regiment, the rest of the disembarked artillery, the rest of the light dragoons, and General Howe’s headquarters.

Lieutenant-Colonel Dalrymple was in command if the trenches thrown up on Staten Island, which is fifteen English miles long and five wide.”

_______________________

Quoted From: Revolution in America: Confidential Letters and Journals 1776-1784 of Adjutant General Major Baurmeister of the Hessian Forces. Translated and annotated by Bernhard A. Uhlendorf. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1957.

All images from: Archibald Robertson: His Diaries and Sketches, 1762-1780. Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library.

The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

After lay-waying in Nova Scotia in early 1777, he participated in the Philadelphia campaign of 1777, seeing action at the Battle of Brandywine and the Battle of Germantown where he was wounded. He was shot in the head and trepanned (a portion of his skull was removed) and fitted with a silver plate to cover the hole, requiring St. George to wear a black silken cap for the remainder of his life. Xavier della Gatta’s painting of the Battle of Germantown depicts a fellow private, Corporal George Peacock, carrying the wounded St. George on his back from the battle (see illustration below). Mansergh-St George recounted:

After lay-waying in Nova Scotia in early 1777, he participated in the Philadelphia campaign of 1777, seeing action at the Battle of Brandywine and the Battle of Germantown where he was wounded. He was shot in the head and trepanned (a portion of his skull was removed) and fitted with a silver plate to cover the hole, requiring St. George to wear a black silken cap for the remainder of his life. Xavier della Gatta’s painting of the Battle of Germantown depicts a fellow private, Corporal George Peacock, carrying the wounded St. George on his back from the battle (see illustration below). Mansergh-St George recounted: